November 11th is almost over, but I wanted to write about poppies, so here I am.

Another day on the verge of departure, another week past, another season, and it’s not like I can call it unremarkable. And yet what drove me to “blog” again is not the world per se, but the idea of a flower I haven’t personally experienced in…two years now? Three? That flower, though – the knowledge that there are poppies growing somewhere – is a call to return, a hailing, an interpellation, and and and…

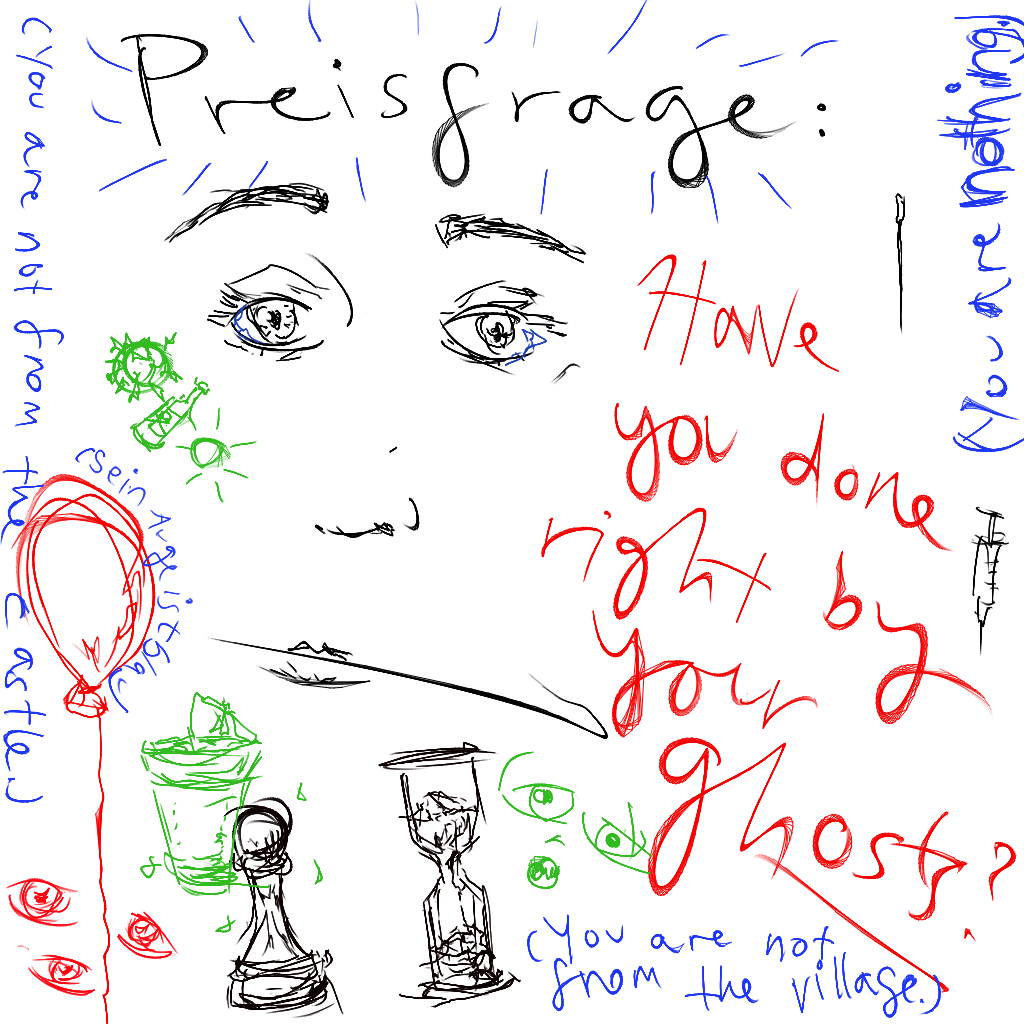

Today is Remembrance Day, Veterans Day, Armistice Day, a day of names that may vary depending on which side of World War I your forebears fought on. And the poppy, particularly the red poppy worn on the lapel, is its flower. In this strange year, eyed by strange ghosts, we renew our international vow to remember.

How to remember?

First, the ghosts that demand attention, the ones we don’t know personally. Then, the ghosts that demand attention, newborn, in gestation. Fields of asphodel, fields of poppies – flowers. I’m sitting in my bed, surrounded by everyday detritus, in the Year of Our Lord 2020, on Remembrance Day, thinking about flowers. That’s rich. And, I suppose, a rambling way of admitting to a distance I’m ashamed of, but not one unique to me.

According to World-O-Meter, the US coronavirus death tally has surpassed 247,000. That’s over twice as many American deaths as in World War I, and over half of our national death count in World War II from 1941 to 1945. Roughly 83 9/11s’ worth of deaths. The human mind, science tells us, begins to reduce faces and names to statistics long before a country is tasked with comprehending that many people vanished, much less remembering them. And still I’m caught off guard by my own inability to feel that loss, to process, and by finding myself a bystander in yet another historical instance of “how did this happen?” On a somewhat tangential note, last year, my Elementary German I students didn’t know what the Berlin Wall was. We Americans have a short attention span, perhaps.

In any case, everything has moved into abstraction. I ask myself again what has happened in the past week:

- Joe Biden was elected President

- Donald Trump refused and refuses to concede the plainly lost election

- Rudy Giuliani gave a speech at Four Seasons Landscaping, sandwiched between a crematorium and a sex shop

- Alex Trebek died

- I read DMZ Colony by Don Mee Choi for class

- My students took a test online

- I ordered more books to add to the growing pile next to my bed

- etc.

The poppy is a salient flower. One must imagine poppies sprouting up between all these shards of half-lived, distant events, swelling into a field. Poppies blinking awake. A promise of red.

Regarding bullet points one and four: Biden’s victory was a moment of lightness, that feeling of coming home after a shift of a shitty foodservice job to make a beeline for the sofa and finally rest your aching feet. The announcement the next day of Alex Trebek’s death felt wrong – Wasn’t my shift over? Wasn’t 2020 finally beginning to look up?

Biden’s election brought talk of an American redemption, a restoration, a return to normalcy and a more welcoming idea of “greatness.” In a way, Alex Trebek (a Canadian!) embodied many of the values of that view of greatness. He hosted Jeopardy! long enough to become a familiar face, a part of that after-shift routine. Occasional jibes and hints of condescension aside, he treated contestants fairly and politely. He, the contestants, and the viewers all took part in an everyday celebration of knowledge for its own sake, wherein luck was at play, but watching the show, you could believe in the merit of the day’s winner. And Alex’s Q&A sessions with the contestants turned winners and losers alike into brief neighbors. A competition, yes, a performance, a spectacle, but there was never a sense of ulterior motives. It was just fun to share in people’s enthusiasm for random factoids. And Alex’s pristine pronunciation made you want to assume he naturally knew the answers to all the questions he asked.

Whenever I’m back home, I watch Jeopardy! with my dad, whose political beliefs I vehemently oppose, every night. I wonder if that will still be the case in the future.

Biden is a re-run of Jeopardy!, so to speak. I’m glad he’s there. But his presence and his victory do not negate the damage of the past four years, and of this year in particular. Alex Trebek will grace my TV screen again; Alex Trebek is dead. He just joined a massive and growing cohort of people who will not see 2021. It’s not too late for any of us to join that cohort. We can’t take anything for granted anymore, not even those of us who were privileged enough to believe for a long time that we were inherently part of an effortless greatness. Since Alex announced his diagnosis, I have actively dreaded the news we got a few days ago, and oddly, I still dread it. The individual tragedy hasn’t registered: I’m lost in the field of poppies again.

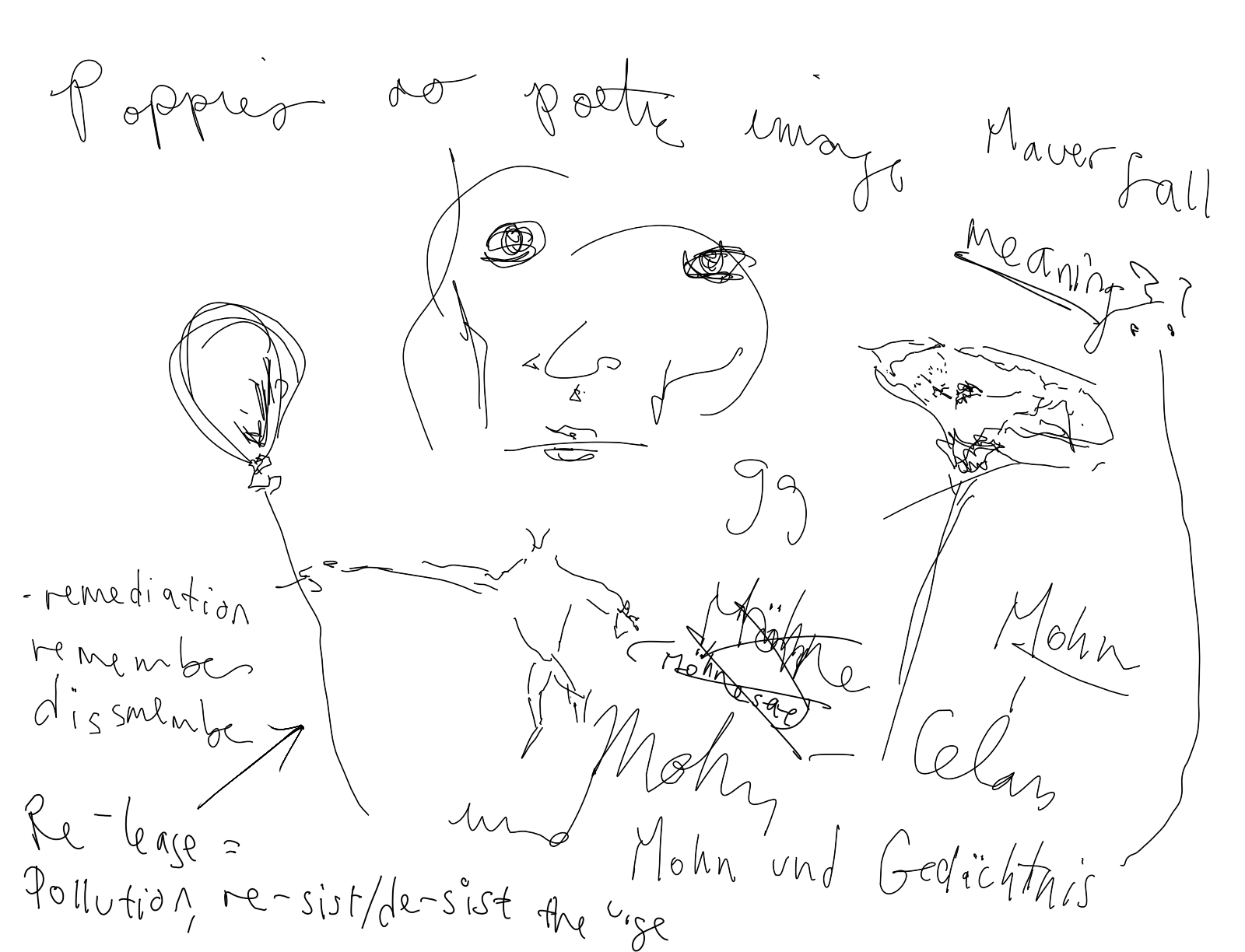

And so I’m writing this without direction, unsure of what it means to remember, to participate in remembrance. Thinking about the poppy as the gorgeous paradox it is in what and how it can mean: producer of opium, tranquilizer, aid to colonization, thing of beauty, killer, sign of life, vision, sign of disorder.

When I was in Dortmund for my English teaching assistantship, I commuted to and from Soest, about a 40 minute train ride from industrial drudge to quaint medieval town and back again. Germany has a population of over 80 million within a land area less than half the size of Texas, that is to say it’s quite densely populated. Although the train passed cultivated field after cultivated field, wind turbine after wind turbine, the only thing I saw (beyond the occasional deer) that felt wild, felt self-perpetuating, was the odd smattering of red poppies edging towards the train tracks. The odd reminder that what you think you know of your tired route won’t stand to time. Or that there’s room for life in the gaps. Anywhere.

(I could never get a good picture of the trackside poppies, which seems fitting enough.)

Consider these paragraphs the petals of a poppy, meandering around some unknown dark center, some promise. Bliss? Oblivion? Cataclysm?

Pretty, too. Consider this still of Kurt Cobain lying in a carefully constructed field of silk poppies and machine fog:

(I did not exist when people whose faces and names I will never know constructed that field. Now the man pictured does not exist. And we will all join him in nonexistence. Perhaps the faceless poppy-setters already have. How strange.)

I have no answers, so today, I’m turning once again to

[at this point I broke off, and now I’m returning a couple days later to see if I can write myself into a hole I can disguise as conclusion. I’ll include some digital doodles as an interlude.]

If I recall correctly, I was going to continue that sentence to talk about images, images in language. A poppy or two from the endless field of invoked poppies. A source of comfort and consternation, something to explain why napping is my favorite pastime when I am at all times conscious of and terrified by the flow of death in my veins. Black center of bloodred petals, vault of silence in every throat, and yet the words exist, and yet some author you read in high school English class can germinate red in twenty-odd teenage heads. A form of collective memory? Yet we’re going wrong and will do so again and again.

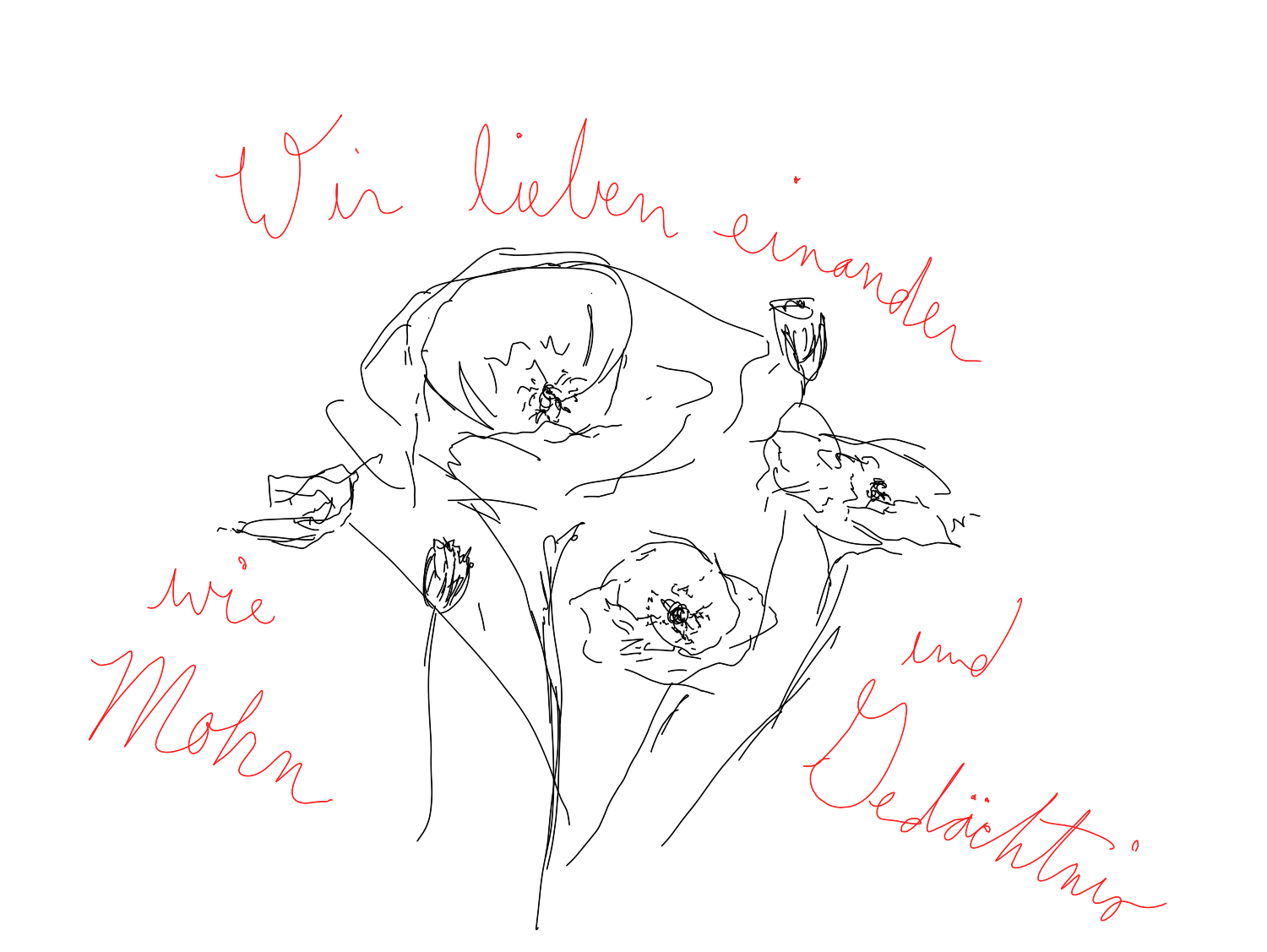

If we can share in tragedy, we can share in beauty. Both belong to memory. And so I’ll cease my rambling by sharing with you some poems with poppies, beginning with my own rough translation of Paul Celan’s “Corona:”

Corona

From my hand autumn eats its leaf: we are friends.

We shell time from nuts and teach it leaving:

time returns to the shell.

In the mirror is Sunday,

in the dream there is sleeping,

the mouth speaks true.

My eye descends to the sex of my lover:

we gaze at each other,

we give voice to dark things,

we love each other like poppy and memory,

we sleep like wine in the mussel shells,

like the sea beneath the moon’s bloodbeam.

We stand intertwined in the window, they look up at us from the street:

it is time that they know!

It is time that the stone concede to bloom,

time for a heart to beat in disquiet.

Time for it to be time.

It is time.

From Emily Dickinson:

It was a quiet seeming Day —

There was no harm in earth or sky —

Till with the closing sun

There strayed an accidental Red

A Strolling Hue, one would have said

To westward of the Town —

But when the Earth began to jar

And Houses vanished with a roar

And Human Nature hid

We comprehended by the Awe

As those that Dissolution saw

The Poppy in the Cloud

Another rough translation (really rough this time, since I tend to get angsty when trying to translate end rhymed poems), this time one of Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus:

IX.

Only the one who has raised

his lyre in shadow as in sun

may know what it means to join

in the song of praise without end.

Only the one who once ate

at the dead’s own banquet of poppies

will never again face the loss

of even the quietest note.

Although the reflections we see in the pond

may often be lost to a ripple,

know the image.

Only within the double-space

will the voices become

undying and mild.

Two Sylvia Plath poems, both of which feel current, the latter of which is one of my favorite poems I’ve ever read, one I can recite from memory and often turn to for comfort:

Poppies in July

Little poppies, little hell flames,

Do you do no harm?

You flicker. I cannot touch you.

I put my hands among the flames. Nothing burns.

And it exhausts me to watch you

Flickering like that, wrinkly and clear red, like the skin of a mouth.

A mouth just bloodied.

Little bloody skirts!

There are fumes that I cannot touch.

Where are your opiates, your nauseous capsules?

If I could bleed, or sleep!

If my mouth could marry a hurt like that!

Or your liquors seep to me, in this glass capsule,

Dulling and stilling.

But colorless. Colorless.

Poppies In October

Even the sun-clouds this morning cannot manage such skirts.

Nor the woman in the ambulance

Whose red heart blooms through her coat so astoundingly —

A gift, a love gift

Utterly unasked for

By a sky

Palely and flamily

Igniting its carbon monoxides, by eyes

Dulled to a halt under bowlers.

O my God, what am I

That these late mouths should cry open

In a forest of frost, in a dawn of cornflowers.

And because I’m so happy Louise Glück won the Nobel, I’ll let her words wrap up this account of confusion:

The Red Poppy

The great thing

is not having

a mind. Feelings:

oh, I have those; they

govern me. I have

a lord in heaven

called the sun, and open

for him, showing him

the fire of my own heart, fire

like his presence.

What could such glory be

if not a heart? Oh my brothers and sisters,

were you like me once, long ago,

before you were human? Did you

permit yourselves

to open once, who would never

open again? Because in truth

I am speaking now

the way you do. I speak

because I am shattered.